World on Water: Where Learning Comes Alive

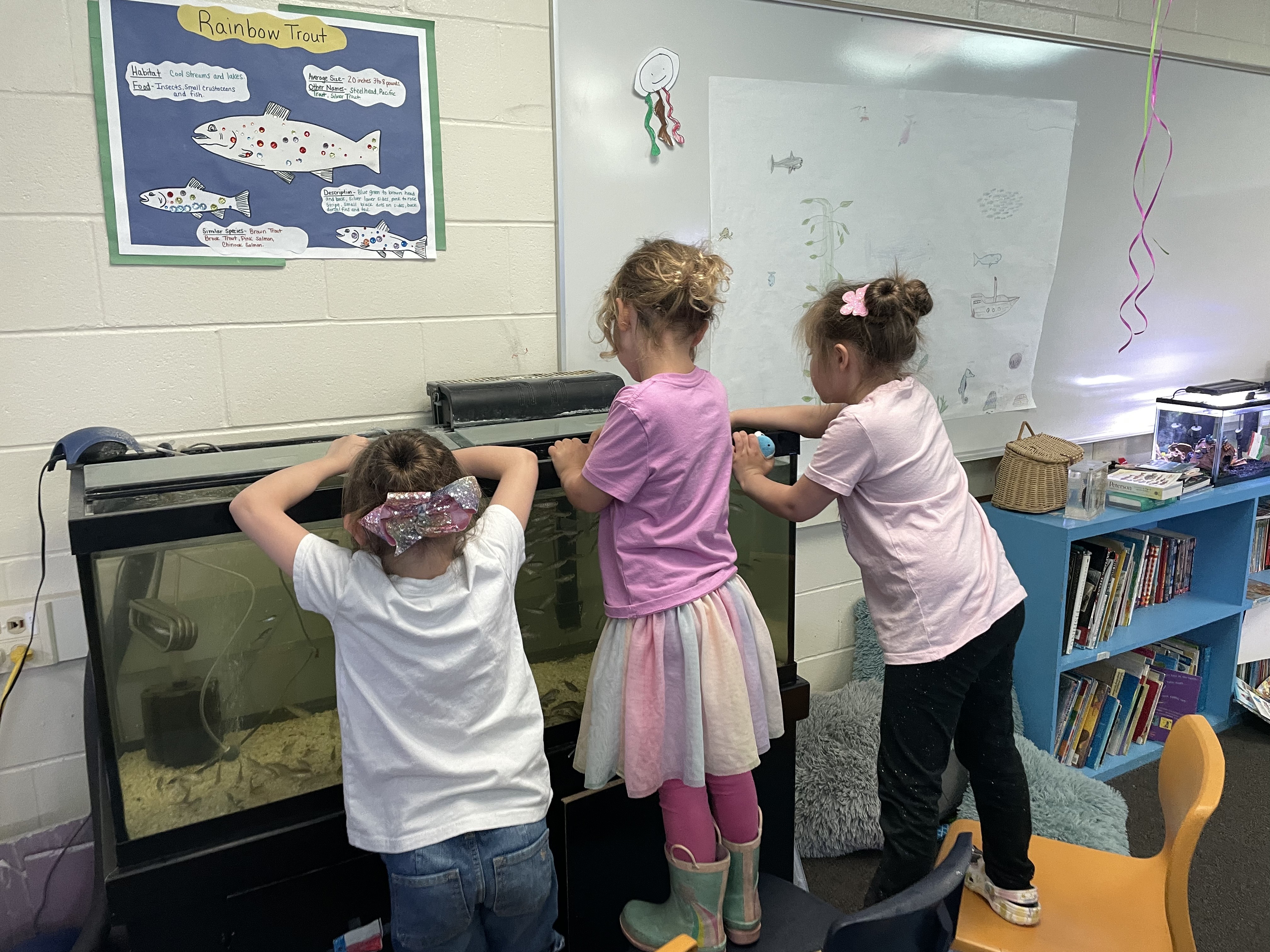

When you step into Mrs. Thwaits’ classroom at Winterquist Elementary in Esko, Minnesota, the first thing you notice isn’t the desks or the whiteboard, it’s the water.

Glowing aquariums line the room, home to trout, turtles, and axolotls. Bubbles rise behind student-made artwork. The air feels calm and alive. Less like a classroom, more like a living ecosystem.

This space is the heart of World on Water, a program created by special education teacher Branda Thwaits, whose work has quietly but profoundly reshaped what school can look like for some of Esko’s most misunderstood students.

When Traditional School Isn’t Built For Every Child

Branda’s students are children with Emotional Behavior Disorders (EBD). In many traditional classrooms, they struggle to belong. Here, something changes. Among the tanks and the water, these children aren’t problems to be fixed. They are scientists, caretakers, explorers—children worthy of patience, compassion, and joy.

One of those students is Maverick.

High-energy, funny, and deeply big-hearted, Maverick’s story reflects a truth many families know well: traditional school isn’t built for every child.

When his behaviors escalated, it became clear to his mother, Kris, and his teachers that he needed something different.

In most classrooms, success is measured through stillness: sit quietly, regulate your emotions, and follow the rules. For students with EBD, expectations like these aren’t just difficult, they’re often impossible.

“In a traditional school environment,” Kris explains, “these trailblazing, free-thinking kids don’t fit in the box. And when they don’t fit the system, they’re pushed aside.”

Branda sees this every day. What’s often labeled as defiance or laziness is, in reality, neurological overwhelm under pressure.

There’s one group of people we’re still allowed to discriminate against, and it’s kids with behavior problems.

Judgment comes quickly. A child melting down in a grocery store draws stares. A student struggling in class is labeled disruptive.

“If I have dyslexia, people understand reading is hard,” Branda explains. “If I’m screaming in the classroom, everybody’s just mad at me.”

But these kids aren’t waking up planning to make life difficult. They’re arriving at school carrying massive emotions, without the tools to regulate them yet.

Nature as a Recognized Regulator

And when the pressure is removed, when the environment changes, something remarkable happens.

“When these kids are in the right spaces,” Branda says, “you don’t see the negatives at all.”

World on Water creates the right spaces.

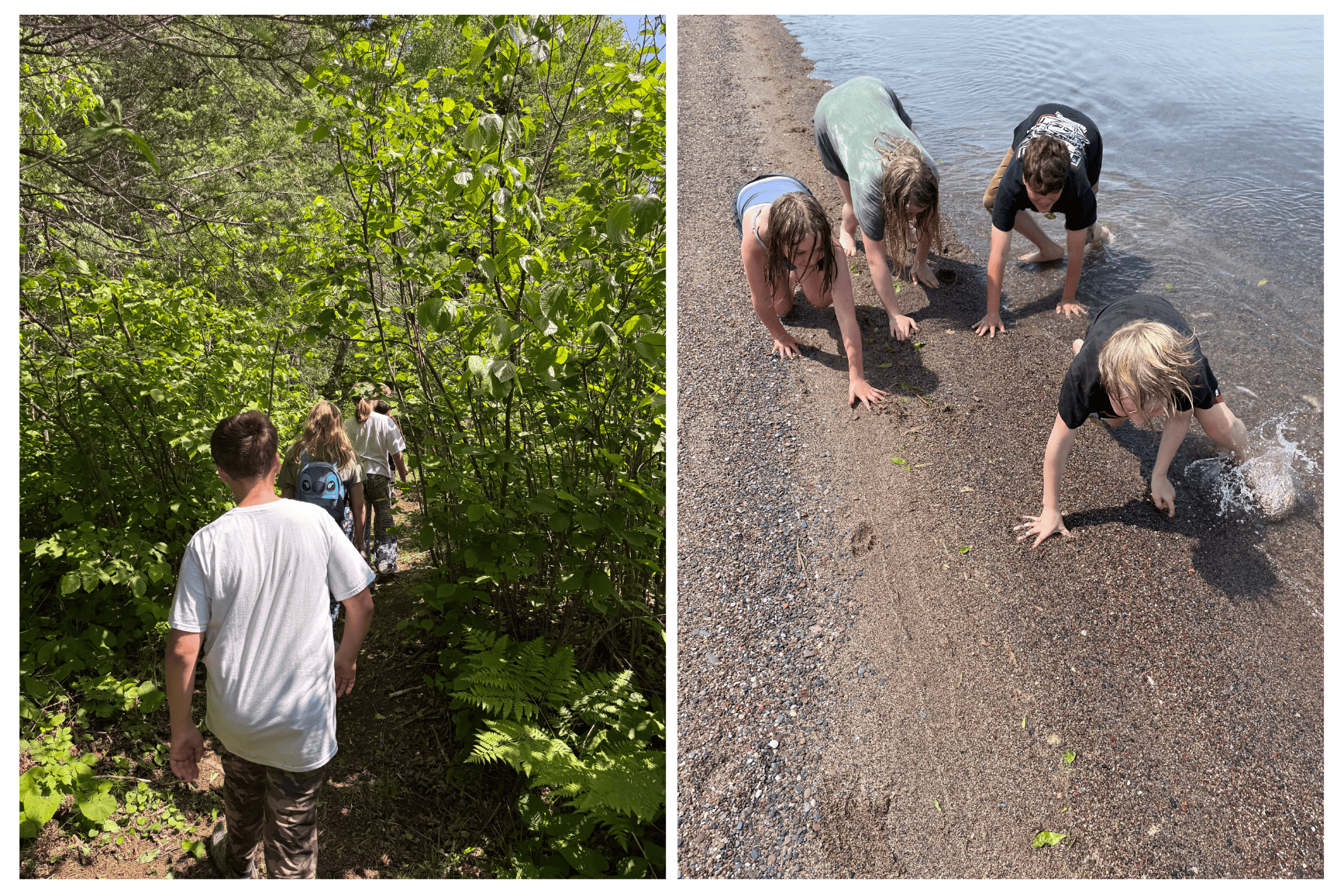

Rooted in Branda’s background as a fisheries scientist, park ranger, and educator, the program takes students out of rigid classroom structures and into nature—canoeing, creek walks, birdwatching, beach days on Lake Superior, and charter boat excursions that offer room to breathe, move, and connect.

Before teaching, Branda worked with the DNR and the National Park Service, bringing thousands of kids into rivers and natural spaces.

“I took probably 10,000 kids into the water,” she reflects. “Not one behavior problem. Not one.”

Nature had always calmed children in ways classrooms couldn’t. World on Water was the calling that brought everything together.

For Maverick, the impact was immediate and lasting.

Where others saw challenges, Kris saw a child who loved making people laugh and dreamed of becoming a billionaire—not for wealth, but so he could help people experiencing homelessness. “What seven-year-old says that?” she asks, still emotional.

Through World on Water, Maverick’s sensitivity became a strength instead of a liability.

Building Confidence and Pride

His confidence grew. His self-talk changed.

“There was no more ‘I’m a bad kid’ or ‘Nobody likes me,’” Kris recalls. “It was all positive.”

One of Maverick’s proudest moments came on a charter boat on Lake Superior, when he reeled in a trophy fish. When his photo appeared in the Duluth News Tribune, he “felt famous”, a moment he still returns to with pride.

But the deeper transformation was internal. World on Water didn’t just change his days. It changed how he saw himself.

Not Just for Kids: Strengthening Families

And the impact didn’t stop with the kids.

“I realized how alone these parents really are,” Branda says.

On trips with families, she witnessed something rare.“ Parents spend the night arguing with their kids after school,” she explains.“ But on the boat? Everything was positive.”

For many families, these moments weren’t just fun, they were healing.

“Knowing there’s a community that sees him is critical,” Kris says. “Branda makes sure families know they’re supported.”

Since launching World on Water, Branda has received countless messages from parents. The thank-yous blur together in volume and meaning. What they share is simple: their children finally feel like they belong.

Made Possible Through Community Partnership

World on Water is fully funded through community partnerships, including support from the Boreal Waters Community Foundation.

Through the Community Opportunity Fund, Boreal Waters has invested $50,000 in World on Water—supporting a program rooted in belonging, dignity, and long-term impact.

“None of this would have happened without Boreal Waters,” Branda says plainly.

A World Where Every Child Belongs

That investment has rippled outward, strengthening families, shifting perspectives, and proving what’s possible when children are met with empathy instead of punishment.

“This program needs to stay,” Kris says. “It’s life-changing.”

World on Water shows us what happens when we stop asking children to fit the system, and instead build systems that fit children.

“They’re thirsty to go where they belong,” Kris says.

Branda hopes her students carry one thing forward: “That they’ll feel better about themselves. That they’ll know they mattered.”

Because when a child feels safe, seen, and supported, the transformation is undeniable.

Just ask Maverick. Ask his mom. Or ask the teacher who built a world where misunderstood children can finally feel at home.